As inflation surges in many parts of the world, some consumers are finding that their money does not go as far as it used to, particularly when they are buying food.

In the US, for example, food became 11 per cent more expensive in the 12 months to April 2022, according to government statistics, while overall inflation over the same period was a more modest 8.3 per cent.

Among foods, animal products have experienced some of the fastest price increases, reports from US media suggest.

For the year ending April 2022, the price of beef and veal went up 14.3 per cent, milk prices rose 14.7 per cent, the cost of chicken shot up by 16.4 per cent, and egg prices rocketed 22.6 per cent. By contrast, inflation among key plant-based foods was in single-digit percentages.

Several factors may explain the rapid rise in the cost of meat and other animal products, including “price gouging”, where suppliers charge more because, for example, competition is limited. Concerns have been raised that the handful of big American meat producers are taking advantage of their dominant position.

But a rapid rise in the cost of meat has not just been seen in the US, and other factors such as grain price increases are also at play.

While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused a surge in grain prices, costs were rising even before this, with fertiliser costs ― which translate into higher food prices ― jumping 80 per cent last year and continuing to rise in 2022.

“It’s grain, in particular, that’s fed to a lot of animals,” says Prof Matin Qaim, director of the Centre for Development Research at the University of Bonn in Germany.

“That means if the components of the input are getting much more pricey, the meat is also going to be much more expensive.”

Changing buying patterns

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3FAZ57KBAZZU2LZ3IVSCUFMMSM.jpg)

In some countries, meat prices are thought to have increased by as much as 30 per cent or 40 per cent, according to Dr Henning Otte Hansen, senior adviser in the Department of Food and Resource Economics at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and author of the book Food Economics.

Heavy food-price inflation often hits people in poorer nations hardest, he said.

“They will have to spend perhaps 80 per cent of their income on food,” he says, referring to a figure that has been reported for Angola in Africa.

In developed nations, a much smaller proportion of household income goes on food, with the figure in the US just 6.9 per cent.

Yet even in such wealthier nations, shoppers are thought to have been changing their buying patterns to take account of increased meat prices.

“As the prices for beef and poultry, in particular, have gone up, consumption has gone down,” says Prof Matthew Diersen, an agricultural economist at South Dakota State University in the US.

“Your dollar doesn’t go as far and that’s meant some consumers have been, I think the trade calls it, trading down. You go from an expensive cut or an expensive type to a more affordable cut or type.

“The problem with that has been that poultry has been a more affordable alternative, but that was affected by some production problems.

“Moving around and changing your consumption pattern has been more difficult in the last couple of years than at other times.”

Bird flu outbreaks in the US resulted in tens of millions of birds being killed this year, disrupting egg and poultry production.

Adopt different diets

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/U6N7F7GFB3XVFTCL3RNJFGEEG4.jpg)

Some consumers may have been switching to other sources of protein, such as beans, Prof Diersen says, while others may have simply been going without.

But meat consumption in the US is still high by international standards. Last year, it averaged a record 102 kilograms per person, possibly the highest figure in the world, according to statistics published by the National Chicken Council.

Meat consumption in other developed nations is also typically much greater than in developing countries but in Europe, in particular, signs of decline are evident as more consumers adopt vegan, vegetarian or flexitarian diets.

“A lot of people in Europe try to reduce their meat consumption for sustainability reasons,” Prof Qaim says.

“Sustainability may be environmental and climate concerns; there may also be, to some extent, animal welfare concerns. All these concerns are increasing with people’s wealth.”

Germany’s Federal Office of Agriculture and Food stated that last year the country’s per capita meat consumption was 55kg, the lowest for three decades. One forecast suggests overall meat consumption in Europe will begin to decline from 2035 onwards.

In developing nations, meat consumption is much lower, although it is increasing as countries become more prosperous. In China, consumption of animal products has more than doubled over the past three decades.

Prof Qaim says in India annual per person meat consumption is thought to be about 5kg a year, while in poorer developing Asian and African nations, it may be in the region of 10kg.

While saying “you cannot condemn countries that increase their meat consumption”, Prof Qaim thinks it would be preferable if developing nations did not eventually rival the developed world in terms of annual per capita meat consumption.

“I hope they don’t, simply because the environmental and climate footprint is so big, our little Planet Earth would tremendously suffer,” he says.

In the shorter term, Dr Hansen suggests that it may not be until 2023 that meat prices tail off, helped by the fact that grain prices have already peaked.

“The feedstuff ― grain ― has started to decrease. This will mean the feed costs for chicken will decrease. In the beginning of next year you will start to see a decrease in meat prices” he says.

Foods that consumers may choose instead of meat

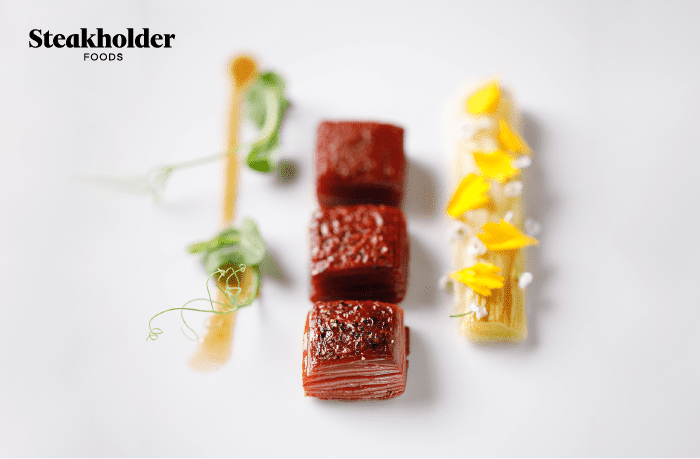

Alternative meats

There has been growing interest ― and a reported $5 billion of investment last year ― in alternative meats, ranging from plant-based fake meats to meats produced from cultured animal cells.

Cultured meats are largely at an experimental stage and have yet to reach cost parity with meats produced from animals, but this is expected as technology improves.

Interest in plant-based meat analogues is not confined to Europe and North America, with numerous companies and products launching in Asian markets.

Whether cell-based and plant-based meat alternatives will be relevant to developing nations is, however, the subject of vigorous debate.

Organisations such as The Good Food Institute, a not-for-profit organisation with its headquarters in the US that advocates for alternative proteins, and which has received funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, have argued that these foods could become important in poorer countries.

Others, such as the International Livestock Research Institute, say that alternative meats are irrelevant to poor communities, many of which have problems of hidden hunger, which refers to inadequate intake and absorption of vitamins and minerals even when people take in sufficient calories.

Plant and insect foods

Consumers looking for cheaper options as meat prices increase can turn to a variety of protein-rich plant-based foods.

“Pulses, such as lentils, and beans and peas are important plant-based protein sources,” Prof Qaim says. “People in India don’t eat a lot of meat, that’s one reason they eat a lot of pulses, and these are good sources of protein.”

He suggests that householders, particularly in developing nations, may look for alternative fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds to augment their diet as meat prices surge.

Insects are also being promoted as potential alternative protein sources, with the European Union approving the use of certain insects as animal and human food in 2021 and 2022.

For example, in February the European Commission, the EU’s executive branch, gave the green light to the use of house crickets and yellow mealworms as human food in frozen, dried and powder forms.

“There’s a lot of talk about insects, but I don’t see the rapid mass movement towards insect consumption,” Prof Qaim says.

“They play a crucial role in some places that may, in the long run, increase. I don’t see that happening in Europe or other parts of the world in the near future.”