Algae, fried insects, and exotic lab-grown meat could all be on the menu.

Over the next few decades, the fate of the world’s food supply will largely be shaped by a number: 9.3 billion. That’s the projected global population for 2050. By then, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that the world needs to have boosted food production by 60% to meet demand.

Where will those extra calories come from? The answer will likely require new approaches to food production.

Land and climate: Agriculture currently uses about 40% of the world’s land and is responsible for 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. It’s possible to clear vast swaths of tropical forests and other areas to make new agricultural land, as nations did at an unprecedented rate throughout the 20th century.

But doing so would exacerbate global warming in two ways: creating more sources of greenhouse gas emissions (such as methane from cattle) and destroying trees, which absorb carbon while alive and release it when felled.

Rethinking the food supply: Feeding a growing population sustainably will require both improving the efficiency of conventional agriculture and inventing new ways to make food.

On the conventional agricultural side, many commercial farmers are already employing methods to increase yield while minimizing environmental destruction, such as using efficient irrigation systems, tailoring fertilizer blends to certain crops and soils, utilizing computers to better apply pesticides and herbicides, and feeding cattle food supplements to lower their methane output.

As for new food production techniques, the future is wide open. Vertical farmers are growing crops indoors, using computers to monitor plant health and efficiently administer food, water, and light. Cell-cultured meat producers are growing real animal meat in labs, all without killing animals. And aquafarmers are growing nutrient-rich kelp and microalgaes, both in natural ecosystems and in bioreactors.

As the 20th century shows, the food supply isn’t fixed — and it can transform quickly. Here are some foods, new and old, that might make it on menus by 2050.

Cell-cultured meat: Grown in a lab, cell-cultured meat isn’t a plant-based meat alternative — it’s real meat.

The process works by extracting a healthy culture of cells from an animal, and then placing those cells into a bioreactor where they can grow and multiply into tissue. After a couple of weeks, the lab-grown meat can be shaped into familiar products, like burgers or chicken nuggets.

While there remain questions about the nutritional value of cell-cultured meat, it’s definitely got the upper hand on the ethics side. The fact that it doesn’t require slaughtering animals also means that the industry could offer some exotic foods, such as lab-grown tiger meat, which one startup may soon start selling.

Companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods have sent the plant-based meat alternatives booming over the past decade. One reason these companies have shot to prominence is that they appeal to both vegetarians and carnivores alike by mimicking the taste, look, and texture of real meat products.

But the future of plant-based foods could also pack entirely new flavors. In 2020, Big Think asked Impossible Foods CEO Patrick O. Brown whether the company had considered creating plant-based dishes that bring new flavors and concepts to the table instead of foods that simply mimic familiar meat products.

“Oh absolutely, and this is something internally, and in our [research and development] team, we love to think about,” Brown said.

Traci Des Jardins, a chef and culinary advisor to Impossible Foods, said creating new plant-based dishes would be something like the vegetarian’s answer to the hot dog (in concept, not taste):

“I can imagine products that we could create at Impossible that would be amazing things that could become as iconic as the hot dog,” she told Big Think. “Because a hot dog really means nothing. It’s just a name that’s been attributed to this thing that goes in this bun. And so, I think there are many, many possibilities, and that we could create all kinds of delicious things that don’t have the environmental impact that animal-produced meats have.”

Legumes: Legumes — whose edible seeds are called pulses — are responsible for all of the world’s beans, lentils, and peas. Pulses are cheap and packed with protein and B vitamins.

But one of the reasons these plants are likely to play an increasingly important role in the global food supply is their sustainability. Legumes can grow in a wide variety of climates and, unlike most modern crops, they don’t require nitrogen fertilizers. In fact, most legumes (famously, peanuts) actually improve soil quality.

There are more than 16,000 legume species in the world, though only a small number are produced at large scales.

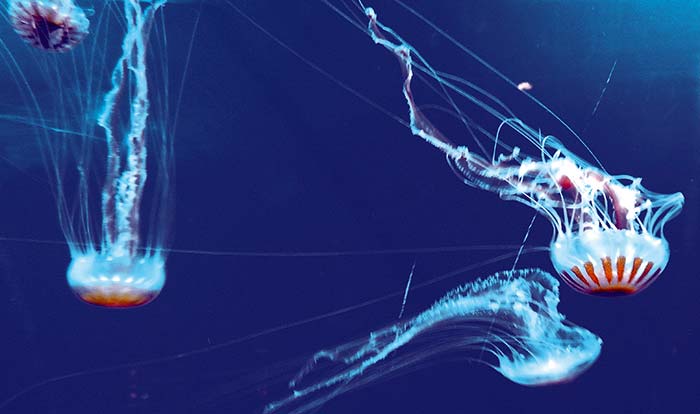

Jellyfish: Jellyfish have been eaten as part of Asian cuisine for centuries. But the invertebrates, of which there are more than 20 edible species, could soon start showing up on Western menus, likely in the form of dried chips or as a cold, pickled product.

Low in fat and rich in protein and minerals, jellyfish pack many of the same health benefits as other fish, but they’re not endangered. In fact, jellyfish populations have been thriving as waters warm, positioning them as an especially sustainable seafood option.

Insects: Nearly 2 billion people worldwide eat insects, a practice known as entomophagy. Sure, the idea of snacking on deep-fried grasshoppers is a hard sell, especially for consumers in Western nations.

But when it comes to farming efficiency, insects outperform just about every other animal because the cold-blooded critters are extremely easy to raise and are far more efficient at converting their feed into protein than common livestock.

Edible insects are often touted as a “food of the future” and the market is projected to grow significantly throughout the decade. But for insects to become a common dish outside of African and Asian nations, marketers will have to figure out how to shift norms enough to rid entomophagy of its stigma in the West. In the meantime, some insect farmers are having a go at raising them for animal feed.

Algae: Kelp, which is a macroalgae, is not only rich in antioxidants and elements like iodine but also one of the most sustainable crops. After all, seaweeds like kelp require no feed and, because they grow through photosynthesis, they capture carbon that enters the oceans from greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere.

People have been eating edible seaweed for centuries, particularly in Japan, where it was once such a common crop that the government allowed people to pay taxes with it. In recent years, aquafarmers in the U.S. have been ramping up seaweed production, with some startups now selling kelp-based burgers, jerky, chips, and pasta.

Beyond macroalgae like seaweeds, microalgae could also soon play a bigger role in the food supply. Microalgae pack similar health benefits to their larger, multicellular counterparts, but they can be grown more easily indoors within photobioreactors.

There are more than 30,000 documented microalgae species, though only a handful are currently used for food, health supplements, and pharmaceuticals. Future research could uncover additional health benefits or new ways to produce algaes.

When it comes to microalgae as a food, the idea is to use it as a supplementary ingredient (like microalgae powder that’s the base ingredient for pasta noodles) rather than eating microalgae alone.

Overhauling the food supply: Feed the world’s growing population in a sustainable way is a mammoth task, but it wouldn’t be the first time society has radically transformed its approach to food production.

In 1900, the world population was roughly 1.7 billion people — a number that would more than triple over the next century. To feed that booming population, the 20th century saw innovations that drastically increased the efficiency of food production, including the introduction of fuel-powered farm machinery, the Haber-Bosch process of producing nitrogen fertilizer from the air, highly productive hybrid maize, selective animal and plant breeding, and genetically modified crops.

Altogether, these innovations helped the food supply grow more quickly than demand during the latter half of the century, reducing global hunger and malnutrition, although hunger was and is still a problem in developing nations.

But while productive, the changes to food production in the 20th century had some negative consequences: processed food became ubiquitous, producers cleared hundreds of millions of hectares for agricultural land, industrial farming practices caused widespread soil degradation, sugar intake spiked, and people (especially in Western nations) began consuming far more calories, mainly from flour and grains and fats and oils.

Today, we have a better sense of how food affects health and the environment, not to mention better technology to improve its production. For the food producers that want to break with the more destructive practices of the 20th century, the overall goal is to make food that’s nutritious, affordable, and sustainably produced.

Still, even the healthiest and most sustainable kelp chip will fall flat if nobody likes it. The most important goal? Make it taste good.