It’s been 10 years since the first burger made from laboratory-grown meat was eaten. So why is it still only available in one country, in one restaurant, only on Thursdays?

In summer 2013, a handful of people gathered in London in what looked like a TV set for a cookery show.

A man in a white coat and chef’s hat basted a burger. The camera filming him cut to a close-up as he spooned oil onto the minced patty. Food critic Hanni Ruetzler perched on a high stool at the end of the counter. At length, a plate with the meat, a side of salad and a rather dry-looking sesame-topped bun was placed in front of her.

Ruetzler was about to taste a £215,000 ($330,000) burger, grown in a lab by a scientist who had dedicated his career to the cause of cultivated meat. That scientist, Mark Post of Maastricht University in the Netherlands, was seated right next to her.

If that wasn’t pressure enough, her reaction was about to be featured on news programmes across the world later that day.

Ruetzler delicately cut into the burger, ignoring the bread, and placed a small browned bite into her mouth. She chewed. The room, crowded with journalists, waited.

As the cameras zoomed in for a close up, she gave the sense of trying to be polite. “There’s quite some intense taste,” she began, before pausing for a moment. “It’s close to meat. It’s not that juicy but the consistent [sic] is perfect.” She then added that she “miss[ed] salt and pepper”, much to the amusement of the studio audience.

Ten years later, as I watch the video of Ruetzler tasting the burger, I’m left wondering whether I will ever get the chance to try cultivated meat myself. Today, lab-grown meat remains far from widely available. But with scientific advice on the need to scale down on meat consumption sparking a wave of interest in meat alternatives in recent years, could it be poised to stampede into restaurants?

“So the industry is fairly new,” says Tasneem Karodia, co-founder of Mzansi Meat Co, a South African cultivated meat firm. “The first burger was made in the Netherlands in 2013. And probably three to four years later, there was a handful of companies. Now, we’re sitting at probably over 100 companies in the space.” Between them, they’re growing lamb, duck, beef, chicken, fish and more. They are also collectively receiving billions of dollars of investment, according to The Good Food Institute, an alternative protein think tank.

But what exactly is cultivated meat?

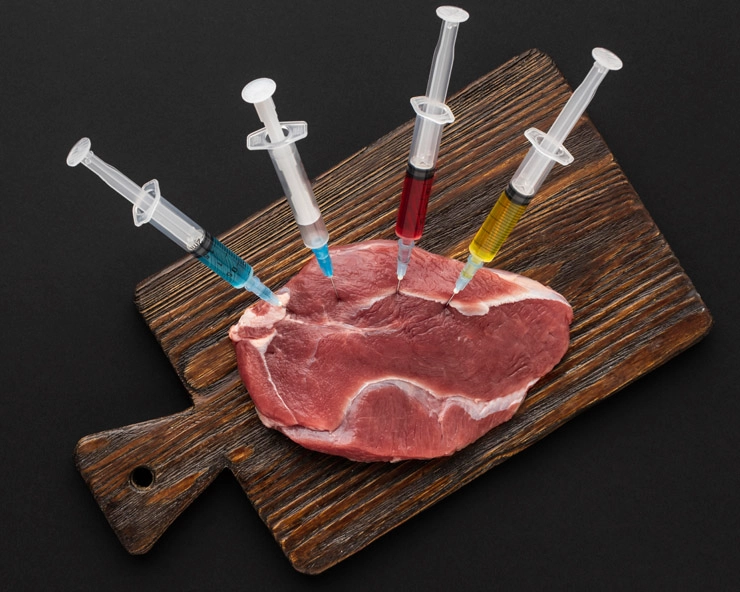

Cultivated meat essentially means “replicating the same process you’d find inside of a cow, outside of the cow”, says Karodia. In other words, lab-grown meat is genetically indistinguishable from the real deal.

The first step in making it is to take a small, peppercorn-sized biopsy from a cow – leaving the animal “up and running afterwards”, Karodia notes. The biopsy is taken back to the lab where it’s put into a bioreactor – a metal vat not unlike those beer is brewed in. It’s full of a nutritious broth that contains all the ingredients that cells need to grow and grow.

Studies agree that cultivated meat will still be higher impact emissions-wise than most plant-based meat alternatives

Karodia tells me her company’s broth contains fetal bovine serum (FBS). This has become controversial as it’s derived from the blood of a cow foetus – meaning a pregnant mother needs to be slaughtered to make it. For that reason, Karodia is looking to replace FBS entirely. Her team hasn’t figured out how just yet, but even if Karodia doesn’t find a way, using FBS will still result in fewer calves, lambs, pigs, ducks and chickens being raised and slaughtered for consumption.

That means you don’t need to use a significant portion of the Earth’s land to plant soy and corn to feed all the animals, according to Josh Tetrick, chief executive of another cultivated meat firm, Eat Just. That, he says, results in fewer emissions. “So it’s a way of eating meat that makes sense for the future.” Indeed, Tetrick sees it as replacing all conventional meat one day.

Several studies and reports from think tanks and consultancies have made similar assertions about lab-grown meat, finding that it could substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions. One study found cultivated meat would produce 96% fewer greenhouse gas emissions than conventional meat. Another found it would reduce emissions by 74-87%. The gains are higher for highly polluting livestock like beef or lamb and less for poultry or fish.

** Click here to read the full-text **